Written and researched by David Head This is the untold

saga of a great nation of people whose names and feats have been

undocumented. These nameless, faceless, hard workers who endured the

physical, backbreaking labor from day to day made the transportation

system work. Although they were excluded from the process of making

decisions, African Americans nevertheless played a major role in

paving a road across the world. As African Americans we should never forget those courageous pioneers who pressed on with their dreams during very difficult times. These creative inventors were determined to succeed against all odds. Each of them has made his aspiration a reality by contributing to the

industrial, social and economic progress of this great nation,

America. To begin this journey we must leave the shores of North America and travel back to our roots across the Atlantic Ocean to the continent of Africa, the

cradle of civilization. We come upon the ancient Cushite empire of

Ethiopia which was the first source to give the world ideas. This

great nation led the way in the unexplored fields of engineering,

science and transportation. It was their skillful hands that raised

mammoth walls, dugout lakes and laid roads that have, endured

throughout the ages. The wheel has been around since the beginning of mankind. It was further developed by the Ethiopians and Egyptians whose empires existed for over three thousand years. They flourished through trade, commerce and military conquest. Caravans of four wheel carts pulled by oxen and horses

carried passengers. Their merchants sailed across the ocean to

India, Persia, Arabia and beyond.

The Phoenicians reigned supreme in navigation from 2700 B.C. to 600 A.D. These dominant mariners were also excellent merchants. The Phoenicians

built large fleets of merchant ships departing from well constructed

ports, they sailed, traded and exchanged goods throughout the

Mediterranean Sea and beyond the Strait of Gibraltar. Their skill

and knowledge of wind and current were extraordinary.

The history of the Moors and their contribution has been long neglected. Rich with commerce and industry, learned in all the arts and sciences, the

Moors developed a culture that would. light up the world from its dark ages. During this golden age between the 7th and 14th centuries AD, their

advances in navigation include lateen sails, astrolabes, and

nautical compasses. Moorish school teachers knew that the world was

round and taught geography from a globe. They produced

expert maps, with all sea and land routes accurately located with

respect to latitude and longitude. Their sailors traveled the length

and breath of the then known world. Saturated with wisdom of the

ages, through its tributaries, the Moors constituted a link between

the ancient civilization and the modern world. It was not by

accident that a Moor named Pedro Alonso Nino was the chief navigator

for Christopher Columbus. From the very

outset of expansion into the new world the inventiveness and labor

of Africans played an integral role. The Black presence was

operative when Nino piloted the flagship Santa Maria to what is now

known as America. George Monroe and

William Robinson were to African Americans who carried mail on the

famous Pony Express. Monroe was also given the honor of driving

Presidents Ulysses S. Grant and Ruthertord B. Hayes along the

dangerous s-curve of the Wanona Trail into Yosemite Valley. For

being such a reputable stagecoach driver, Monroe Meadows was named

in his honor. It may never be

known just how many inventions credited to whites were actually

created by their African captives. However, the number of inventions

make by Black people increase after the Civil War. By then, there

were at least 200 operating railroads. Many Blacks took part in the

backbreaking labor of connecting the Atlantic to the Pacific, the

first trans- continental railroad in 1869. Let’s take a

closer look into the lives of the great Black inventors who improved

the transportation system through their creative ingenuity. Such

inventions as the automatic lubricator helped save time and money.

The rail industry can give credit to two runaway slaves when Elijah

McCoy was born on May 2, 1843. He developed a small cup with a valve

mechanism that could supply oil drop by drop to the moving parts of

machinery. McCoy devised many different lubricants that were so

efficient they became known as the “Real McCoy”. When discovered he

was Black many executives refused to buy his inventions. But that

was virtually committing economic suicide. From 1872 until 1915 most

locomotives in the United States and in many foreign lands used his

invention. Then there was

Andrew Jackson Beard who worked-at a railroad yard in Alabama. While

there, he became familiar with one of the most dangerous

occupational tasks in the world-joining railroad cars. A worker

stood between two railroad cars to guide the linking pieces into

place and insert a metal pin that held the pieces together. Quite

often the heavy cars crushed the middle man before he could drop the

pin into place. On November 23, 1897, Beard eliminated the need for

a worker to stand in the no-man’s land by creating the “Jenny

Coupler,” a device that automatically joined cars by simply bumping

them together. The name Granville

T. Woods may be alien to the average American. He most certainly is

one of the giants left out of the encyclopedia and documentaries on

transportation. His saga is one of the great legacies African

Americans have given to American history and culture. Granville T.

Woods was an electrical genius whose inventions were pivotal in

advancing the Industrial Age. Denied meaningful employment, Wood’s

innovative spirit was being held back because of racial prejudices.

His determination drove him on to success by opening his shop, Wood

Electrical Company in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1881. Woods Telegraph

Induction Relay System saved lives and prevented the almost routine

train wrecks that occurred during that era. In 1885, Wood patented

the telegraphony, a device that allowed telegraph stations to send

messages via Morse Code and orally over the same lines. In 1887, he

created a synchronous multiplex railway telegraph which allowed

messages to be sent to and from moving trains, enabling train

conductors and engineers to report of hazard on tracks ahead, but

more importantly to avoid collisions. Wood also solved the

electrical problem of controlling the speed at which mechanical

parts moved by the amount of electrical current. By inventing a

device called a dynamotor, which regulated motor speed with much

smaller resistors that reduced the heat and the electrical waste.

Although Granville T. Woods never became a household name, his reputation as an electrical genius spread throughout the industry. ‘The giant, Thomas

Edison, was so impressed by Wood he tried hard to recruit Granville

by offering him a prestigious position in his company. Granville

preferred to be his own boss and declined Edison’s offer.

Lewis Latimer’s carbon filament which is the device that empowered the electrical light bulb was another major invention on September 13, 1881. The

positive dynamics of this discovery would generate and ignite the

beginning of the modern age. These inventions, with widespread

implications, improved the lives of all Americans. In addition to

convenience, let us not forget the lives electric lights have saved:

warning and guiding signals improved and kerosene lamps which could

cause major fire damage on the wooden ‘el” trains of that era were

eliminated. The world in deeply indebted to Garret Augustus Morgan for his contribution to transportation safety. Morgan was a versatile inventor who witnessed a gruesome accident between a horse-drawn carriage and an

automobile. Feeling something had to be done, Morgan devised a

signpost that would regulate traffic coming from all four directions

of an intersection. By creating a rectangular block stop and go

rotating traffic signal. When the blocks were at half-mast this

alerted everyone approaching the intersection to proceed with

caution. Morgan also proposed having the sign electrically lit so

they should be visible at night as well as during the day. Garret A.

Morgan received a patent for his traffic signal on November 20, 1923

at the age of 47. It was quite evident that these remarkable inventors lacked education in addition to resources and capital to attain their goals. A young Frederick Jones is a perfect example. Jones, fascinated by machines, developed

a burning desire to work with them. Never receiving the proper

educational training, Frederick had a keen, inventive mind and an

ability for understanding machinery. Jones designed a light compact

and sturdy unit in the forehead of a truck right above the cab. This

invention led to the formation a new firm called Thermo King.

Jones patented a total of sixty-one inventions. Many of his ideas were soon adopted for use ir1 railroad cars, cargo ships and airplanes. Frederick

McKinley Jones’ inventions boosted the transportation industry

tremendously in making food products available by easing its

distribution. These brilliant, innovating pioneers opened a

passageway of progress to the twentieth century. The New York EraAs the wheels of steel turned northward to the great metropolis of New York, there

laid ahead a giant industrial revolution. Here was an opportunity

for a better living. It was estimated that by the end of 1918, more

than 1 million Negroes had left the south by rail.

New York was known as the gateway of the world, a national leader in transportation with its landmark Grand Central Terminal, the monumental

Pennsylvania Station and, of course, the N.Y.C. subway system which

is the largest underground system in the world. In the midst of it

all was Granville T. Woods whose ideas and inventions did much to

change and modernize transportation. Woods make it possible to go

from inefficient, costly steam engine-driven trains to cleaner,

cheaper and more effective trains run by electricity. The World Book

Encyclopedia states there are two ways to get the current from the

powerhouse to the train: by overhead wires above the track and from

a third rail placed beside the track. In 1888, Woods set

up an overhead conducting system for the electric railway. In this

system, a pole form a train or trolley would draw the electricity

needed to run the locomotive’s motor from a power line running

overhead. This became a familiar sight in many cities.

Granville was called to New York in the 1890s to begin work on the subway. The

work was completed in 1904. His design of an electrical third rail

and air brake revolutionized the technology of rail transportation.

In 1889, Grand Central Terminal was becoming a safety problem. The enormous amount of smoke from its powerful steam engines was blinding pedestrians.

The city demanded: electrify the trains or move the operations out

In 1904, the NY entral began work on a third-rail D.C. e lectrification of its lines

into Grand Central Terminal. The Long Island Railroad and

Pennsylvania Railroad likewise adopted a 650-volt O.C. third-rail

system. While the owners extended their lines and reaped huge

profits, employees were vastly underpaid. They endured poor living

conditions and being non-unionized, they were at the mercy of their

employers. A. Philip Randolph, father of the Black labor movement, began to organize the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters on August 25, 1925. Underpaid and enduring extremely, long working hours, Randolph guided the BSCP to a decent, well-paying job. The Pullman Company labeled Randolph a communist and fought his union every step of the way. Yet Randolph never compromised his principles or goals of the Brotherhood. After twelve long, grueling years of tearing down racial barters, on August 25, 1937, the Pullman Company signed a contract with the nation’s first Black union. The union was the voice of the porters. African Americans assisted in the construction of the subway system from its inception. They found employment in the rigorous cut and cover operations in addition to the dangerous and difficult task of

tunneling. These sandhogs risked their lives daily tunneling through

rock, clay, sand or water. These men faced quicksand, cave-ins,

suffocation, flooding, drowning, fallen rock and pockets of gas that

would cause a man to pass out. They faced the added threat of

suffering from the dreaded bends which could permanently cripple or

even kill. With sledge hammer, pick ax and shovel removing rocks and dirt, these strong-back Black men helped lay the foundation. Singing while they

worked: “Oh, Joe! Come on let us get this job done, ugh bam. Oh,

Joe! Come on let us get this job cone, ugh bam.” This great

engineering feat of connecting major arteries throughout the

tri-state area, which is still being utilized today, is truly

amazing. These tunnels reduce traveling and maximized the efficiency

of trains. The I.R.T. began operation on October 27, 1904. The majority of its workers and supervisors were Irish. A few Blacks were hired as porters. There

were no promotional opportunities. It was not until 1935 the

Independent (IND) subway system hired the first Negro conductor.

Advancement for African Americans was tenuous and slow.

In 1943, during World War II, the Board of Transportation began hiring a large

number of provisional employees. Black women were employed to drive

buses and trolleys. Some were used as ticket agents, Their efforts

kept the transit system operation smoothly.

Bus operator Mr. Thomas Granger was the primary source in laying the track for his brothers and sisters to come across racial barriers. Risking his

job, he fought tooth and nail with management and union. Granger

received no satisfaction so he decided to go the political route by

contacting Adam Clayton Powell, New York’s first Black elected to

City Council Powell was a young, dynamic leader, and an agitator for

justice who guided the residents of Harlem to protest second-class

treatment. Adam lead the boycott campaign to break discrimination

that existed throughout the labor unions. His slogan,”don’t buy

where you can’t shop,” was highly successful. These tactics forced

the NYC private bus companies to hire Black drivers for the first

time. Hiring policies were changed so a driver had to take a test to get a job. Keypunch operators went to school to be reclassified. Ernie Barksdale became

the first African American Location Chief. Joe Legree, a retired

captain in the Air Force in maintenance was assigned to supervise a

training school to reorganize and upgrade the Negro mechanics.

When dealing with union activity in transportation, two men are worthy of praise. Intelligent and articulate with the ability to transform ideas into

reality, John T. Burnell and Roosevelt Watts were both men of

action, sincerity and concern with the needs and aspirations of its

members. At the time, Michael J. Quill began to organize the

transport workers during the early 1930s, John enthusiastically

worked alongside him. John Burnell’s first job was a bus maintainer

for the Fifth Avenue bus lines. But his real strength lay as a

motivational speaker who could galvanize members on key issues that

affected their daily lives. Burnell raised the conscious level of

the transit worker, stressing an education agenda Emphasizing that

one must work to attain his goals, John devised and

initiated the Educational Program for Transit Employees which

remains intact today. A tireless, unselfish, dedicated worker,

Burnell improved integration in job placement. Above all, Burnell

believed in one race, the human race. In 1979-1980,

Burnell was assigned to the NYC Transit Authority office of Labor

Relations in addition to the N.Y. State Department of Labor as an

arbitrator. Roosevelt Watts was a man of great distinction, genuinely committed to helping his people and always loyal and faithful to the causes of the T.W.U. In 1942, Watts began his illustrious career in transportation as a

street car operator. Then as shop steward, he became known as a man

of his word, who stood up for his fellow operators’ rights. Watts

was elected Section Chairman for Brooklyn Bus in 1945 where he

served for 13 years. A bright and

well-liked person who paid attention, Watts took advantage of each

opportunity when it presented itself. Roosevelt was elected to the

T.W.U. local Executive Board in 1960. Watts never forgot where he

came from and he reached back to bring his people along with him. He

continually gave advice and guidance whenever or wherever necessary.

Finally, in 1975, Roosevelt Watts became the first African American

to hold an executive position in the International. Watts also

became the first African American to hold a position as Vice

President in T.A. Surface. In addition, he held the title of

Executive Vice President of T.W.U. local 100. Roosevelt Watts, a

visionary person looked forward to seeing the day when local 100

would have Black President. On March 29, 1962,

Fifth Avenue Coach abandoned its operation to the NYC Transit

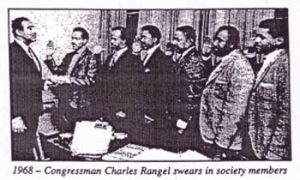

Authority, This was the birth of MABSTOA. In 1968, a group of 6 men

felt they were not receiving any recognition. They began to unify

and mobilize all African American Transit employees. Thus the

Society of African American Transit Employees was born. Mr. Adolph

Roberts, their audacious leader, spearheaded this fight for equal

rights. As a group, they were now able to get the Transit

Authority’s attention. The TA didn’t like their ideas and these men

were targeted, harassed and penalized by management.

Committed to their cause, this would only addressed hiring and placement practices, working conditions, promotions, disciplinary action and termination.

By exposing and confronting management on these issues, improvements

could be made. In 1971, Marcy Gibson,-an alumni of the Society of African American Transit Employees, became the first Black Chief Executive Officer for the Transit Authority. In the process of these confrontations, a young, quiet warrior would emerge whose leadership qualities would grow over the years. A spiritual man of inner vision whose patently planned agenda would place him at the fore front of various key positions in the Transportation Workers

Union. A lengthy, yet timely ascension to the top would place Mr.

Willie James at the pinnacle of an exemplary career. By becoming the

first African American president of the TWU since its inception, Mr.

James now leads one of the most powerful unions in America. He

continues to push forward and fight for the rights of all Transit

Workers, and remains committed to unity, activism and respect for

all of his members as we enter the 21st century. Let us not forget

the real unsung heroes in the background bearing the brunt of the

work load, keeping the wheels turning in this fast-paced, high

pressure, stressful city. The men and women who operate routinely at

their work sites as porters, token booth clerks, conductors,

carpenters, bricklayers, motormen, mechanics and bus operators. They

make the T.A. the number one transit system in the world work. The African

American presence in transportation extends throughout the history

of the transportation industry in America. Their epic contributions

have transformed the global experience in traveling. The African

American was not just a mere spectator of world history but a

creative originator since the genesis of mankind. Today, the freedom

train has knocked down old, entrenched racial policies over the

years. Opportunity to grow is everywhere, the challenge lies within

each individual to build upon our proud legacy.